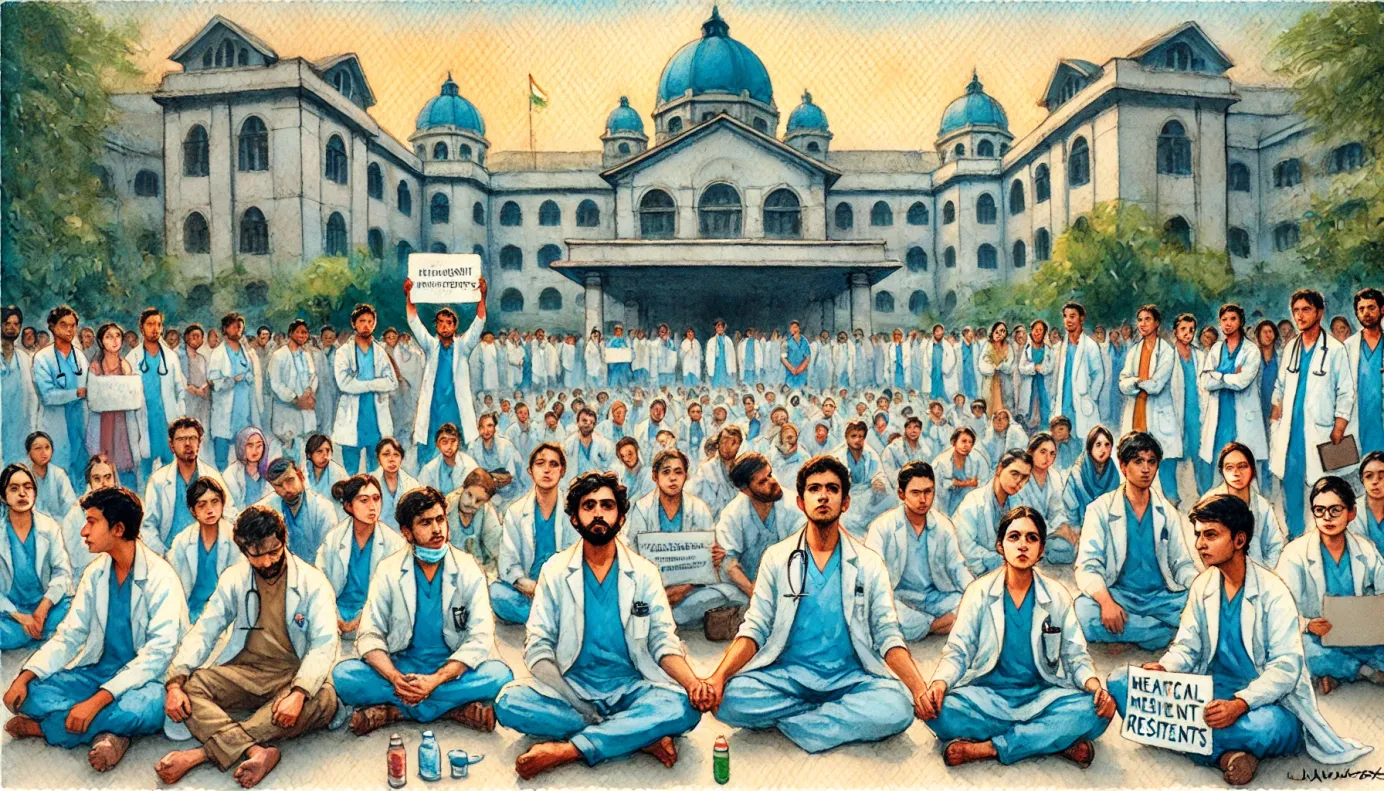

Striking for Principles: The Strike Against Capitation Fee Colleges by Resident Doctors in 1984

Strikes by resident medical doctors are a rite of passage, but it is only once in a lifetime that the strike is based on non pay-hike principles.

Audio

Text

For most medical resident doctors in public medical colleges and hospitals, participating in a strike has become a rite of passage. Every 2-3 years, resident doctors’ associations like MARD (Maharashtra Association of Resident Doctors) go on strike for better living conditions, pay, and security.

The playbook is standard - I wrote this in 2006 and have reproduced it again on this site.

First week - enthusiasm, rallies, hunger strikes, street plays

Second week - some of the less enthusiastic residents go home, some default, some start studying for their exams on the sly

Third week - government threatens loss of term and enthusiasm dips.

Fourth week - most residents want to get back to work.

Fifth week - strike is over

If the strike is shorter, then all of this happens faster.

Strikes are rarely due to other reasons. The 42-day RG Kar strike resonated with non-doctors and doctors alike, as it was a spontaneous uprising against a heinous crime.

However, this wasn't the first time resident doctors struck for a non-pay hike "cause".

Forty years ago, resident doctors in Maharashtra went on strike because the Govt, led by Mr. Vasantdada Patil, gave permission for 31 capitation fee medical colleges to be setup in Maharashtra. Today, for-profit high-fee private colleges are a normal occurrence. But up until 1984, there were barely a handful of private medical colleges, mainly in Karnataka and this announcement causes a furor in the medical community.

Admission to medical colleges used to be merit-based, dependent on board exam performance, and hardly anyone “paid” for a seat. As a student in LTMMC in 1984, my fees were Rs. 600 per term (around Rs. 3,000 today when adjusted for inflation). It felt wrong that someone would pay Rs. 30,000 per year (Rs. 1.3 lakhs today, adjusted for inflation) for a medical education.

There was a similar proposal for engineering colleges. Very little written online material survives from that time, but there’s one article (unfortunately behind a pay-wall) from India Today that summarizes the reasons behind these decisions and another by Sanjay Nagral, published in the Medico Friend Circle Bulletin in Dec 1984. Much of what follows is based on these articles, conversations with friends, my memories and Dr. Jackie Lalmalani’s MARD President’s Report from a couple of years later. (If anyone has access to other material or remembers anything else, do email me at bhavin@bhavinj.com)

On June 23, 1984, there was a token strike, and from July 10, 1984, an indefinite strike. I was a II/II medical student, and we all joined the strike because the teachers had to work in the hospital and we had no classes. A friend and I were sent by Dr. Jackie Lalmalani, the strike leader, to Pune to meet students from other medical colleges at B J Medical (I think) and form the Maharashtra Medical Students Association.

Jackie and his colleagues led the statewide strike. There were street plays, morchas, relay hunger strikes, and attempts to sensitize the public and newspapers to support our strike. It wasn’t easy.

There were threats of rustication and letters sent to the resident doctors and their parents, that if they didn’t join back, their MD/MS registrations would be canceled. I first saw guns in my life in the RMO Quarters in Sion when they were smuggled in to protect the leaders, due to a rumor that “goondas” were going to assassinate them.

Many Deans supported capitation fee colleges, arguing for more private medical colleges to meet future needs, as the government lacked resources to create them. However, there was no room for dialogue. Any resident doctor not joining the strike became a social pariah. The IMA promised money but didn’t deliver, according to Jackie. A strike delegation met PM Indira Gandhi, who supported the strike. MP Pramila Dandavate also denounced capitation fee colleges in the Lok Sabha. But it didn’t matter. The CM and cabinet were determined to proceed with capitation fee colleges, backed by those starting them and big money. We didn’t stand a chance.

On 6th August 1984, the strike was withdrawn with just a “no victimization” assurance from the Govt.

A writ petition had also been filed and Adv. E P Bharucha fought the case, but the Supreme Court’s judgement eventually favored capitation fee colleges. The only caveat was that the Medical Council of India (MCI) would oversee them, which was a boon, because once the MCI recognized these colleges, it legitimized them and their proliferation.

I hope the RG Kar strike does not meet the same fate as most medical resident strikes and that concrete steps are taken to prevent harm to medical students, interns and residents in every teaching college and hospital in this country. The current residents need to establish a system for perpetual monitoring of the situation even after they leave and newer residents take over.

Strikes are hard for both patients and resident doctors, but they’re necessary because without them, no authority listens. Those in charge know that resident doctors are transients and a resource that can be mined ruthlessly, because they can get away with a lot of rubbish that wouldn’t be allowed in any other industry using white collar talent. Until the authorities become more proactive, even though the playbook of a resident doctors’ strike doesn’t change, this strike-cycle will continue for years to come.

Bhavin's Writings Newsletter

Join the newsletter to receive the latest updates in your inbox.